I usually write about the lives of my forebears once they have arrived in Tasmania, not before. But George Ransley and his wife, Elizabeth Bailey, are worth making an exception. Put it down to the number of historical, journalistic and literary accounts, poems and perhaps even paintings devoted to George’s pre-emigration activities.

Most of the written accounts are highly fanciful. The first credible author to tackle the subject was retired naval Commander and Coastguard officer, Henry N Shore, later Lord Teignmouth, in 1902.1 By then George Ransley and his generation were dead and most of the dust had settled. Shore was also writing long enough after the event to be able to access official records which had previously been classified as secret.

All the sources agree on at least one point: George Ransley, my great great great grandfather, was a notorious and successful professional criminal. He led a smuggling gang, the Aldington Blues, which stole on a grand scale from the Crown and took up arms against its representatives, killing some and wounding more.2 If not for the fact that their motivation was financial, not political, they might these days be described as terrorists. And while there is little to be said in their defence, with the hindsight of nearly 200 years the story of George Ransley and his gang does make for a ripping yarn.3

But first we need to go back a bit.

Elizabeth Bailey

I have written elsewhere on this site about Elizabeth Bailey’s family as I am also descended from her sister Rhoda, almost 10 years Elizabeth’s junior. For the reasons discussed then it is impossible to be sure of Elizabeth's parentage but it seems likely she was born to Mersham couple, Samuel Bailey and Mary Highstead (or Highsted). If so, Elizabeth was baptised on 27 March 1785 in her parents' village.4 This is a reasonable, although not perfect, fit with the age given at the time of her death in Tasmania.5

Mersham had a population of 571 in 1801 with its land half in pasture, mostly for sheep, with a further third planted to 'turnips, barley, wheat, beans, peas, clover and oats'.6 But the village may not have been the quiet backwater which could be deduced from its pattern of land usage. Seven kms up the road lay Ashford, home to a sizeable military barracks. Goods landed on the south Kent coast traversed Mersham then Ashford to reach London, 80 kms from Ashford.

Rhoda was only one of Elizabeth Bailey´s siblings.7 Two of the others, Samuel and Robert, ended up in the dock with George Ransley, as did her uncle John Bailey.8 Officially though, the Bailey men were farm workers, like most of their neighbours, living respectively at Bilsington, Mersham and Bonnington.9 The Bailey women too no doubt performed at least some seasonal farm work in addition to the unremitting labour of running a rural household.

George Ransley, a Ruckinge Ransley?

It is equally difficult to be sure when and where George Ransley was born, and to whom. Assuming his age at death was correctly recorded, he was born around 1779-80 and almost certainly in the part of Kent, close to Romney March, where he spent his adult life. He seems to have had at least one brother.10

The most solid evidence for a specific birthplace comes from George himself. On arrival in Van Diemen's Land (VDL) he named the south Kent village of Ruckinge as his 'native place.'11

Baptisms are the usual proxy for an absent birth certificate. However surviving church records are not always complete, the age of a child at baptism could vary considerably and not every child was baptised. With those caveats in mind, researchers have identified two candidate baptisms for 'my' George Ransley.12

The first is the son of George Ransley and Hannah née Barnes, baptised at Kenardington on 13 February 1785. This village is only a few kilometers to the west of Ruckinge so it is feasible a Ruckinge couple may have chosen it for a baptism.13

The second is a George Ransley baptised in Ruckinge itself, the son of Robert and Martha Ransley, on 26 August 1791.14 If this is the right George he would have been around 11 years old when the minister wet his head – not impossible but perhaps less likely.

Ruckinge was described in a 1799 survey of Kent as a 'dreary unpleasant place' and its inhabitants as the 'poorer sort of people'.15 Contemporary diarist J A Finn went further, portraying it as a place where: 'much illegal traffic was carried on and every species of vice nurtured, the sabbath day disregarded, heathenism and all immorality practiced, [sic] cards, dice, dominoes … were the general order of the sacred day.'16

The Ruckinge Finn described was also a hotbed of smuggling and two Ransley brothers, Ruckinge natives, had been hanged for highway robbery and horse stealing in the 1780s - hence the highwayman on the village sign above.17

A connection between these two miscreants and George Ransley has often been asserted but the evidence remains circumstantial. Still, with namesakes like that …

Elizabeth and George

The chief (legal) economic activity in Ruckinge was farming so unsurprisingly George Ransley's earliest employment was as a farm servant.18

From those humble beginnings he progressed to work as a carter, or wagoner, at Court Lodge Farm, Aldington, maybe 6 kms as the crow flies NE of Ruckinge.19 Court Lodge was and is a substantial establishment, having been a hunting lodge and home away from home for the Archbishops of Canterbury in the 15th and 16th centuries and still appears in its own right on modern maps.20

Court Lodge Farm was handily close to Aldington Frith where the Bailey family were living providing plenty of opportunities for George Ransley and Elizabeth Bailey to become acquainted.21 Perhaps as a young carter George did a bit of moonlighting for the local smugglers – his knowledge of horses and access to wagons would have been highly valuable to anyone needing to move goods around on the quiet.

Elizabeth Bailey fell pregnant in her early 20s, presumably to George Ransley. Whether marriage had already been under contemplation was irrelevant – you didn't get a Bailey girl into trouble and escape the consequences. Brother Samuel measured 5'11” and Uncle John loomed two inches taller against George not quite 5’7” so the Baileys were a force to be reckoned with.22

A marriage was arranged for 14 February 1809 at St Rumwold's Church, Bonnington, a village midway between Court Lodge and Aldington Frith.23 George and Elizabeth's daughter, Matilda, was baptised five months later. The christening was not held at Bonnington but at the parish church of Bilsington, yet another village overlooking Romney Marsh.24 It was to be the first of many such happy occasions.25

The Other Local Industry

From the time the export duties were first imposed in England (on wool in the 13th century) there had been people bent on evading them.26 The same went for the array of taxes that applied to luxury goods imported into the country such as spirits, tea and tobacco.

The embargoes imposed on French goods during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) only made what was euphemistically called 'free trading' more profitable. It is estimated that in the early 1800s tobacco could be sold in England for ten times what it cost to buy on the continent of Europe.27

‘Free traders’ came up with an almost infinite number of ways to conceal contraband: modified barrels, false bottoms in ships, pouches sewn into clothing for lighter items such as tea, the list is long. They also used a wide array of sail and row boats to transport goods the short distance across the English Channel. It is not my intention to go into detail here, fascinating though it is, but I can recommend the excellent website www.smuggling.co.uk/ to anyone who wants to read further.28

Proximity to French ports, London as a market less than 100 kms away, and a seagoing tradition gave the south of Kent unbeatable advantages from a smuggling point of view. A longstanding and probably specious set of arguments also held that certain local ports, including Folkestone and Dover, were entitled to duty free status for services rendered to the Crown in centuries past. These arguments no doubt helped reinforce the widely held view that smuggling was not really a crime.

While local people knew what was going on they often had an interest, financial or otherwise, in keeping their mouths shut or even actively covering up for the free traders. Whatever their views on its morality, all understood the economic significance of smuggling to their brothers, cousins or neighbours especially during the high unemployment which followed the demobilisation around 1815 of the 250 000 soldiers and sailors who had been recruited to fight Napoleon's armies.

'There was very little going on here in winter time, and it was a difficult matter to get a job.'29

Most government attempts to stamp out smuggling between England and the Continent had failed for lack of resources and had been hampered by a local population prepared to protect the free traders.30 But the end of the Napoleonic Wars freed up the Royal Navy and from 1817 naval men and matériel were deployed to blockade the Kentish coast.

The Aldington Gang

The smuggling gang based at Aldington made its first appearance in official reports in 1820.31 One of its number, Cephas Quested, was hanged in 1821 when an armed clash left a naval officer dead and eight others on the government side wounded.32 Casualties must have been incurred among the smugglers too but for obvious reasons there is no record of them.

There was a lull in activity after Quested's execution but the gang became active again in the middle of the decade. In March 1826 Lieutenant Samuel Hellard, a blockade officer, reported to his superiors on 'These public robbers [who] belong to the parish of Aldington ... headed by George Ransley, a smuggler of notoriety in this neighbourhood'.33

Why George Ransley?34

As every reader of crime fiction knows, a criminal needs to have both motive and opportunity.

In George Ransley’s case one motive was clearly financial. His marriage with Elizabeth was proving highly fertile and with eight children by 1823 there were a lot of mouths to feed. The Ransleys would struggle to make ends meet from small farming or from George’s work as a carter. Smuggling on the other hand was a lucrative business. The profit from a single cargo of 300 tubs of spirits is estimated to have been in the region of £450-500.35

George and Elizabeth's eldest son, George jnr, reported later that his father took up smuggling 'first in about 1812 to make some more money'.36 This suggests that George was not involved in the trade before his marriage but given the prevalence of smuggling locally this may not be strictly true.

In addition to the money, George must have relished proving to Elizabeth that he shared the courage and daring of her family. He may also have been motivated by the increasing challenge of outwitting the authorities.

And the helping hand of opportunity?

There is a certain amount of folklore about George Ransley's transformation from humble carter to the criminal mastermind nicknamed 'Captain Bats.'37 Some writers refer to a lucky find of hidden goods which financed the building of the Ransley house, the Bourne Tap at Aldington Frith.38

Whatever the truth of the matter one contemporary summed it up neatly:

People said he found money somewhere : anyhow, he knocked off work quite sudden-like and took to smuggling, and never did anything else after that. He had a nice horse and cart, almost directly : it was thought that he had stolen the horse and cart, though of course it was not known. Anyway, he had a deuced nice mare.39

George Ransley must have had extensive hands on smuggling experience but he distinguished himself from other potential gang leaders by his combination of strategic and business acumen. Sourcing the goods, calculating when tide and weather would be right, identifying safe houses and markets for goods, recruiting and paying a workforce of up to 80 for each run, all of this took networks and nous.40

There was also the French side to manage. It appears that George would make the trip across the Channel as readily as a farmer would take his sheep to market, albeit perhaps with a bit more discretion:

'He used to smuggle gin, brandy, tobacco and sometimes playing cards from France. He would cross over by packet [regular ships carrying letters, post and passengers] from Dover and buy a boat over there that would carry about two hundred tubs, each holding three and three quarters gallons.41 The boat would be manned by sailors kept by father for the purpose; they lived mainly at Folkestone. After buying the goods, he would arrange for them to be brought over to England at a certain time and place … [which could be] along the coast between Rye and Walmer'.42

Even Henry Shore, by no means on the side of the smugglers, was forced to acknowledge 'a degree of discipline which one would never have suspected amongst so heterogeneous crowd of rustics' singling out the efficiency of the gang's arrangements for evacuating and dealing with their dead and injured.43

Ransley Inc.

It has been estimated that a tub of spirits bought in France for £1 could be sold to wholesale customers in England for £4.44George Ransley went one better. At the Bourne Tap he could sell smuggled grog to gang members, watered down as much as he chose, and recoup in the process a good part of the money he had paid to the men who had helped smuggle it in the first place!45

It is not hard to imagine Elizabeth Ransley, 'a fine woman, strong' helping out at the Bourne Tap when she was not looking after her gaggle of children - three girls and six boys by 1826.46 One third hand account suggests Elizabeth was fond of a drop of gin herself, but all agree that George himself preferred making money out of booze to drinking it.47

George and Elizabeth were ably seconded by their older children. If daughter Matilda's later career in VDL is anything to go by she would have been quite capable of tapping a keg, or anything else required. One local interviewed by Henry Shore recalled it was not unknown for the young Matilda to dress up as a man and 'go to the waterside for goods with the rest of them.'48

The next in line, George jnr, was definitely up to his neck in gang business, reputedly keeping the accounts as well as driving one of the carts used to whisk the goods away to their hiding places.

Captain Bats could also rely on members of the extended family. Brother-in-law Samuel Bailey was his second in charge and seems to have specialised in organising beachside security, probably backed up by his own uncle John. For tactics Samuel could draw on his naval training, having served on (and deserted from) the Royal Navy’s HMS Bulwark earlier in the century.49

Another brother-in-law, Richard Higgins, helped with the carriage of the smuggled goods, contributing at least one cart to the Ransley transport 'fleet'.50

What Was George Really Like?

Reminiscences about George Ransley were collected many years later by the indefatigable Henry Shore from men and women who had been acquainted with him.

This could have been enormously helpful to a biographer but with the lapse of time (usually around 70 years) the accounts diverge considerably, even as to George's physical appearance. Some remembered him dressed in short jacket of the type typical of sailors, others were sure he got about most often in gaberdine, a type of over garment or smock. Nevertheless there are some common threads: George Ransley was a connoisseur of horses; abstemious when it came to alcohol; and consistent in paying his men.

The overall impression is of a disciplined entrepreneur with a keen eye to business. Wounded gang members were cared for and widows not left to starve – if only because to do otherwise might have encouraged informers. Stealing from locals in the gang's later years was probably done without his blessing as it 'would never have suited his business ... He wanted to associate with all parties.'51

Some details of George’s physical appearance have also survived. There is little in them that would make him stand out in a crowd - brown hair, blue eyes, almost 5’7”, a couple of minor scars – other than the novelty of a double row of teeth in upper jaw.52

All Good Things …

As the naval blockade started to bite Kent smugglers had to become better armed and organise on a grander scale. The Aldington Gang was no exception. The tubmen, those on the beach unloading and transporting the contraband, had previously been defended by a 'fighting party' armed with wooden cudgels, or bats. Now the fighting parties began to carry firearms. The navy’s men toted guns and cutlasses. It was always going to end badly.

The advent of firearms was a turning point in another way. It seems that the power that came with carrying a gun went to the heads of some gang members who started to steal from the locals. It’s likely that George Ransley disapproved of these excesses but was unwilling or unable to put a stop to them.

'they got robbing everyone and breaking into houses. They sawed through the door of Scott, the grocer's, twice, and carried off a load of stuff. If anyone was killing a pig they would break in and steal the stuff … Aldington was a dreadful bad place in those days.'53

'They used to carry fire-arms and go about 20 or 40 of them in a body. We were afraid of our lives that they would come in when we heard them passing at night, shouting and swearing and making a pretty row.'54

Not exactly behaviour calculated to keep the populace onside. Moreover some locals who had few qualms about evading customs duties took quite a different attitude when it came to shooting at rank and file blockade officers who were simply doing their job.

The Final Showdown

Tragi-comically the skirmish that sealed the fate of the Aldington Gang took place amongst the bathing machines on Dover Beach fronting Marine Parade but it was anything but comical for those involved.

The Kentish Chronicle of 1 August 1826 reported on an encounter between smugglers and the blockade that had taken place two nights before:

a smuggling boat heavily laden with tubs of spirits, [brandy and gin] arrived off Dover, and in a short time the crew, with the assistance of several other men, attempted to run the cargo. A man, however, belonging to the Blockade service, preremptorily ordered them to surrender, if not he would fire; the threat was only laughed at by the smugglers, and the man immediately discharged his pistol in the air, while the smugglers unceremoniously set to work and removed the whole cargo, consisting of 200 tubs, which were secured by several persons on the beach, and the boat immediately put off. We regret to say the moment the preventive man fired his pistol for the purposes of obtaining assistance, one of the men on the beach fired his and shot the poor fellow through the head.55

The 'poor fellow' concerned was Quartermaster Richard Morgan and he did not survive being shot through the head. A reward of £500 was offered for information that would lead to conviction of those responsible but at first no-one came forward.

The British Admiralty had already sent a legal agent to Dover whose mission was to gather evidence to prosecute George Ransley and his associates. Shore identifies him as Charles Bicknell, Solicitor to the Admiralty, whose seniority indicates that Ransley's activities were of significant concern to the powers that be.56

Initially Bicknell had little success but a month after Quartermaster Morgan's untimely death one of the Aldington smugglers was captured in the course of another run. This man, Edward Horne, turned informer, or ‘approver’ in the terminology of the day.57 His evidence, that of another smuggler James Bushell, and of a small number of 'civilians' was enough to justify the issue of arrest warrants for Ransley and key gang members.

The apparatus of the pre-Victorian criminal justice system then swung into action.

Bow Street runners Bishop and Smith were despatched from London to supplement the resources of the blockade under the command of Lieutenant Hellard.58 On 16 October 1826 this team of crime busters set out from their coastal base, Fort Moncrieff at Hythe, and marched to Aldington, arriving around 3 am.

There were enough of them to be able to stake out each of the target houses and strike more or less simultaneously. The watch dogs at the Bourne Tap had their throats cut and George Ransley, the legendary Captain Bats, was taken in his night attire.59 Not one for futile heroics George put up no resistance but some claim a teenage girl (the irrepressible Matilda?) tried to launch a warning cry 'out of an aperture in the roof'.60

If she did it was to no avail. Taking the precaution to handcuff George Ransley 'to one of the stoutest men in the party' Hellard gave the order to arrest a further seven gang members living nearby, including Elizabeth Ransley's brothers Samuel and Robert Bailey.61

This motley band, presumably all trousered once more, were marched back to Fort Montcrieff.62 The arrested men were immediately transferred to HMS Ramillies, the navy warship commanded by the officer commanding the coastal blockade, Captain Hugh Pigot. There had been cases of sympathisers managing to free arrested smugglers from town gaols and this time the authorities were taking no chances.

For similar reasons the Admiralty was unwilling to entrust committal proceeding to local magistrates, notorious for their leniency towards smugglers. Under the watchful eye of Messrs Smith and Bishop the eight Aldington men were instead bundled into the Ramillies' tender and sailed up the coast to the naval base at Deptford (London).

Committal Proceedings

At the end of October 1826 George Ransley, Samuel Bailey, Robert Bailey, Richard Wire (or Wyor), William Wire (or Wyor), Thomas Gillian (also Gilham), Charles Giles and Thomas Denard appeared before Sir Richard Birnie, [imgs avail] Chief Police Magistrate at Bow Street, to test whether prosecution evidence was strong enough to warrant a trial.63

The accused were described as ‘stout determined fellows … [with] the appearance of labouring men’ whereas Ransley ‘looked like a farmer’ as befitted the brains of the outfit.64

At committal much emerged about the events leading to Richard Morgan's death. Bow Street being a favourite haunt of journalists, readers of newspapers in London and the provinces thrilled to accounts of gunplay on the beaches of Dimchurch and Dover riposted by cutlass-wielding excise men. This ‘crowd of rustics’ from Kent was attracting national attention.

Despite Birnie remarking that the evidence against the men was not strong and the determined efforts of their defence counsel, Mr Platt from Ashford, in the end the magistrate played safe and opted for committal. Influenced by the Crown’s assertion that ‘there was not a single gaol on the sea coast of the county of Kent safe; every one of them had been broken into, and smugglers rescued at one time or another’ Birnie committed the men to London’s Newgate prison to await the next Kent Assizes.65

East Kent Assizes, Maidstone

We have Henry Shore to thank for this preview of the trial:

Rumour … had thrown such a glamour of romance and mystery over the exploits of the Aldington smugglers that the disclosure of all of the circumstances of their career was awaited with the keenest anticipation, while additional zest was imparted to the occasion by the prospect of a great public execution … such as was witnessed by thousands on a former occasion.66

For Shore nothing less than the ‘supremacy of the law’ was at stake. If that was not enough there was also every chance there would be half a dozen new widows in the Aldington district the following month.67 The Solicitor-General himself with two other counsel was prosecuting while the indefatigable Mr Platt was assisted by a Mr Clarkson in defence.68

In the event the trial itself before Mr Justice Park was a bit of a fizzer, especially from the point of view of anyone keen to know who was directly responsible for Midshipman Morgan’s death.

The accused were duly brought up before the judge on Friday 12 January 1827 before a packed court. Not unexpectedly all pleaded ‘not guilty’ to the murder charges.

Less predictably they then went on to plead ‘guilty’ to lesser charges relating to assembly, firing on customs officers and smuggling at Dymchurch, Walmer, Deal or Hythe according to the evidence the Crown had on each. With guilty pleas no further evidence needed to be heard before Judge Park could go on to pronounce the sentence of death which went with such charges.69 Folks did like a hanging in those days. [img of register showing death sentence]

General consternation? Well no, as in the best tradition of court room dramas a deal had been done. By who knows what magic Platt had convinced the prosecution he could get his clients to put their hands up for smuggling charges if they, the Crown, would use best endeavours to have the obligatory death sentences commuted.

Platt’s gamble paid off and King George IV commuted the Aldington men’s death sentences to life transportation all round.70 The principal aim of breaking up ‘as daring a gang of ruffians as ever defied the laws of their country’ had been achieved without stirring up unrest by executing those who had, in their own way, provided a fair bit of local employment.71

Transportation Across the Seas

George Ransley with some of the gang were held on the hulk Leviathan at Portsmouth before embarking for Van Diemen’s Land in April 1827.72 The voyage of the Governor Ready is described in more detail in the story of Richard Higgins and Rhoda Bailey and is not repeated here. It is worth noting though that George remained healthy for the duration of the voyage and did not have to call upon the skills of the ship’s surgeon.

The Home Front

Back in Aldington Frith Elizabeth Ransley’s prospects looked grim. Her husband was to be exiled to the other side of the world along with a brother, a brother-in-law and an uncle. As the icing on the cake she had given birth to her tenth child, also Elizabeth, after George's arrest and perhaps even around the time of his trial.73

The eldest children, Matilda and George jnr, were old enough to be earning a living provided work could be found. Some of the others could have helped around the farm if their father had been there to run the property. But the Ransley family budget had come to depend heavily on smuggling income and the farm was not enough to keep them all, or at least not in the style to which they had become accustomed. The cost of paying lawyers Platt and Clarkson and anyone else who had needed to be paid must also have severely drained the family's resources.

Soon Elizabeth Ransley and her family were officially living on the charity of the parish of Bilsington, as was her sister Rhoda Higgins and Mary Giles, the wife of smuggler Charles Giles.74 The obvious solution was to find a way to join George in his place of exile.

George Ransley, Convict

The convict system was a great leveller. In England George Ransley had owned his own farm and pub and run a redoubtable gang of smugglers. He was a celebrity in the district and beyond and many households relied on the wages he paid to make ends meet. But to the VDL convict administration he was simply convict number 471, a resource to be deployed as usefully as possible and at the least possible expense to the government.75

We know that of the 190 convicts arriving on the Governor Ready in August 1827, 138 were assigned to settlers with the remainder either retained for public works, ill or sent for further punishment at Macquarie Harbour.76 George Ransley, classified as 'farmer and ploughman' must have been sent into private service immediately but unfortunately there is little in George's record about how he spent his first years in VDL.77

He does appears on a list of 'Farmers and Ploughmen' assigned to settlers, namely a John Smith of Hobart and then a Mr Monckinton.78 However this information does not take us very far: John Smiths are notoriously difficult to trace and I can find no sign of a Mr Monckinton or similar in VDL before the 1840s.

Life with the Smiths and the Monckintons was not destined to last in any case and by January 1829 George Ransley had been sent up the valley of the Derwent River into the service of Scottish settler George Thompson, proprietor of the picturesquely named Charlie's Hope estate at Plenty.79 So began the long association between the Ransley family and Tasmania's Derwent Valley.

A Policy of Family Reunion

The British Government had instituted a scheme to pay for the wives and families of selected convicts to join them in the Australian colonies.80 It was not open slather, the convict had to have been of good behaviour and be able to support his family. This meant holding a ticket of leave or, failing that, a master or mistress who was prepared to take on the convict’s family.

Luckily the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land at the time, Colonel Arthur, was a great believer in the reformatory powers of this scheme.81 So much so that he was apparently given to forwarding applications from convicts who were, strictly speaking, ineligible.82

Even in this favourable climate it is still somewhat puzzling that Elizabeth Ransley and her children fetched up in the Thames port of Woolwich as would-be emigrants in August 1828 when Governor Arthur’s letter of recommendation was not written until the following October.83 It seems unlikely she would have taken to haunting the docks without something substantial to go on so she must at least have had word from George saying that his master, presumably George Thompson, had supported the application.

Despite this irregularity Elizabeth was allowed to board the female convict transport Harmony with her ten children ranging from Matilda, 19, to baby Elizabeth, their bedding and the family’s worldly goods packed into 4 boxes. The ship sailed in September 1828 with Elizabeth’s sister Rhoda Higgins and a number of other Aldington wives and children aboard. Either these women had great powers of persuasion or the authorities were swayed by the representative of the Bilsington parish, Mr Gurr, who having spent £25 of poor relief funds 'to get clothes for the smugglers families at Woolwich', was no doubt very keen to get the lot of them off the parish books.84

The Harmony was a well-run ship and with one tragic exception the voyage appears to have passed off without incident.85

The exception was Elizabeth Ransley jnr. Already a sickly child who had required regular attention from the village dispensary, baby Elizabeth was on the sick list a month into the voyage with severe diarrhea and all that goes with it. Despite Surgeon Clifford’s best efforts and prescriptions of warm baths and flannels, arrowroot and opium (!) the child’s condition continued to deteriorate. She died off Santiago, the largest island of Cape Verde,86 on 18 October 1828 one of only two deaths on the voyage.87

Destination Charlie's Hope

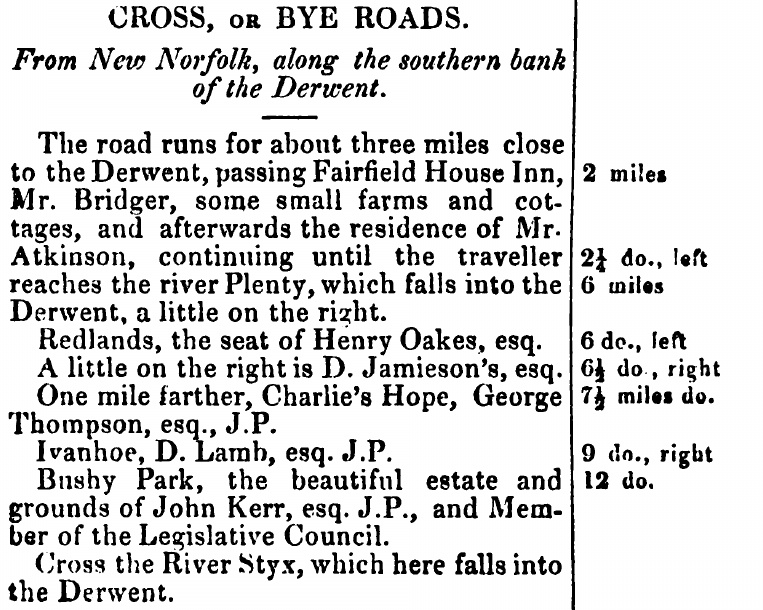

Arriving in Hobart Town at the end of January 1829 Elizabeth Ransley was reliant on her husband to arrange transport to his place of assignment on the River Plenty, more than 40kms to the north west. It can’t have been an easy task to load wife, nine children and the family’s good and chattels onto a single bullock cart, the most likely mode of transport. To get an idea of the route to Charlie's Hope we have a description from 1833:88

So that's the neighbourhood, esquires to the right of them, esquires to the left of them. Most of those with whom the Ransleys could expect to socialise must have been employed or assigned at the Thompson estate or at neighbouring properties.

Scotsman George Thompson had been farming at the River Plenty since at least 1822 so he must have been well established by the time of George Ransley's arrival c.1828.89 Even so it's hard to imagine Thompson’s convict workforce could have knocked over a whole 1000 acres of native vegetation by then so Ransley probably had to spend a fair bit of his time flushing recalcitrant stock out of their hiding places.

The property was of enough consequence in 1830 to merit the appointment of its own constable under the authority of the New Norfolk police district.90 The homestead by whose name, Cluan, the property is now known was not built until 1837 so accommodation for owner and servant alike was presumably pretty rough and ready in the Ransleys’ time.91

It was not an entirely masculine world though even from the beginning. Mrs Thompson had emigrated with her husband and she was no doubt the mistress of at least some female convict servants. But women of any kind were still in short supply and it may be that the prospect of the services of Elizabeth and Matilda Ransley was an inducement for the Thompsons to support their application to emigrate.92 The Ransley boys would also have been easily employed on the farm with perhaps only the youngest, Edward, 5, completely exempt from regular tasks.

The First Tasmanians

Although the first to put up a fence or plough the land, George Thompson and his ilk were not the only people using the land along the Derwent. Local historian KR Von Stieglitz gives an account of stone knife making in the vicinity of Charlie’s Hope so it is certain that Aboriginal Tasmanians frequented the area.93

The Ransley family arrived at the time settler violence towards the indigenous population (and vice versa) was at its height. This is too big a topic to do it justice here but it’s certain that the white fellas on the Plenty River had their anxious moments. Elizabeth Ransley could have been excused for questioning the wisdom of bringing her children into such an environment.94 While her own family was hardly a stranger to violence, an undeclared guerilla war waged by a largely unseen enemy was another kettle of fish.

The climate of rumour and fear is well described (and satirised) in this letter reprinted in the Colonial Times.95 It's long, but also a rare contemporary account of events occurring at Charlie's Hope so I've taken the liberty of quoting it at length.

About the middle of the day on Sunday, just as we were preparing for dinner, .............. arrived from New Norfolk breathless, and looking as white and trembling as though he had seen a ghost, and hastily entered the house, and casting his eyes every where around, as though apprehensive of pursuers, said in a hurried perturbed manner, 'I have some bad news to tell you.'

You know, that for my part, having seen so much of the world as I have, I am not now very easily thrown off my equilibrium, and perhaps not appearing at the moment to partake of poor..............'s fright quite so eagerly as he had expected, he stared at me with a sort of surprise, and repeated in a more energetic tone, ' I have some bad news for you, the blacks are all coming, they are on the hills all around, I have been to Mr. Thomson's, and I don't know what they haven't done.'

Well,' replied I, ' I am glad your news is no worse, for it was plain enough that something or another had frightened you, long before you reached the house , but set down , you are safe now, at all events, and let us know all about it.'

'Safe ! do you say,' be exclaimed, ' Why there are at least a hundred of them some say two. One of their leaders has been taken, and the parties are everywhere in pursuit of them. I have brought you a supply of ammunition, and now I'll be off, if you please, directly to Hobart Town, as I would not stay here for the world.' …

The long and short of what he had to tell me, stripped of all embellishment was, that one day last week an Aboriginal youth went to Mr Thomson's asking for bread, when he was immediately taken, and proved to be one who had already been in our hands, but had made his escape , and it was reported that the lad, who could speak a little English, had given information of there being a considerable party in the neighbourhood.

This occurrence, inconsiderable as it was in itself, was however enough to set rumour's tongue at work, and what with the alarms of old women, the fiery impetuosity of young men, and the readiness of all to believe whatever is said, our little district became, within a few hours, one scene of stir and bustle. In the course of a few hours, one more hardy than the rest, having dared to go so far as his next neighbour's dwelling, established a code of signals between each other-the firing a gun - the blowing of a horn the lighting of a bonfire - or even the more simple and all expressive coo-eh being settled to be used, according to the situation and circumstances of the several inhabitants.

All this happened on Sunday, and these measures being adopted, Monday passed over quietly, and although many a look out was given throughout the day, and many a ' Run, Jem, you little varlet you, and see if the blacks be a coming,' was dinned into the ears of some of the unbreeched urchins around us, by their watchful mothers or grandams, Monday night came, and still no appearance of the Natives.

But Tuesday brought with it, a sad termination of this state of repose from previous alarm, for scarce had the sun half reached its meridian, when a messenger ran through the district at full speed, spreading the direful intelligence that the Aborigines were in great force, two miles the Hobart Town side of New Norfolk - that they had rescued the man previously taken - had murdered the guard who had attended him, with I scarcely know what besides, the catalogue being so dreadful.

I listened to all this, with a nonchalance that was evidently very provoking to him who told it, and when he had finished his story, expressed my determination to proceed to the spot, where the affair was said to have taken place. Those around me, thought I was mad, and said all they could think to dissuade me, but I was sceptical upon all I heard, and could not conceive such a feeling as fear, with any rambles in the neighbourhood stated to have been the scene of action. So accordingly I went, unarmed and unattended. ...

At length, however, I reached the spot, and found things just as I expected. The lad who had been taken at Mr. Thomson's, had contrived to make his escape, between New Norfolk and Hobart Town, from the constable who had him in charge, and the latter apprehensive doubtless, of the consequences to himself, had stated ... that he had been set upon by two other Natives who darted suddenly out of the scrub, and knocking him down, had rescued his prisoners.

This story, however, plausible as it might at first seem, failed in certain essentials towards obtaining for it, credence; and none more strongly than that, the marks of one man's footsteps were clearly discernible along the road, up to a certain point, when they entirely ceased to be apparent, but no additional footsteps either at the spot described by the constable, or elsewhere, could be traced, as must have been the case, had two other Natives been there. In many other points, the constable's story exhibited similar discrepancies; so that, should you and my other friends at Hobart Town, hear the atrocities of the Blacks in the neighbourhood of New Norfolk and be alarmed for my safety, rest assured I am safe and well and that it is all 'Much ado about nothing’."

If the Colonial Times’ correspondent treated the subject with levity, there is no doubt the danger to Europeans in the outlying districts was real.96 In the early months of the year there had been several incidents reported: families burnt out, settlers and their servants speared, some fatally. Many of these incidents occurred around Ouse and Bothwell, further up country than Charlie’s Hope but not far enough away for comfort.

It’s hard to know how much George Ransley feared attack by Aborigines. Given the extent of Thompson’s property he may have worked well away from the relative safety of the main farm buildings and it was well known that shepherds and their huts were prime targets for Aboriginal attack.97 Even if George wasn’t worried for himself it would not have been unreasonable to worry about the safety of his family.

Arthur’s Black Line

By the Spring of 1830 Governor Arthur felt compelled to take drastic action. His plan, known to history as the Black Line, was to send more than two thousand armed men out into the bush to try to 'subdue,' capture or kill the remaining indigenous population.98 Convict George probably approved of Arthur’s aim of moving the Aboriginal population to parts of the island where farming interests would not be compromised but like many he may have been less convinced about the strategy for getting them there.99

The Line was designed to round up Aboriginal Tasmanians and herd them at gun point through the bush like so many refractory sheep. It was led by soldiers supplemented by volunteer settlers, convicts volunteered by their masters and Ticket of Leave holders who were conscripted for the occasion (ask not what your country can do for you …). As it happened the weather that Spring was particularly unpleasant and by all accounts the Line was a miserable experience all round, even on the British side.

George Thompson had business interests round the Clyde River where numerous clashes between Aborigines and stockmen had been reported. He and his Clyde neighbours urged that ‘every sinew of the Government should be exerted to extend ... protection to the Colonists’ and bring ‘under due subjection the Aboriginal tribes of this island’.100 It seems almost certain he would have contributed convicts to the Line but would George Ransley, now nearly 50, have been one of them? I was dubious.

In this frame of mind I started trawling through a murky microfilm in the Tasmanian Archive Office.101 Well into it there is a list of names dated 18 November 1830 of the men who made up the Lower Clyde parties under the command of Captain Vicary of the 63rd Regiment. Vicary had been ordered to start from Hamilton, cross the Clyde River and ‘occupy the eastern bank of the Ouse [River]’.102

Right at the top of the page in the list of party leaders is one George Ransley. A ‘G. Ransley’ also appears in the ‘Volunteers’ column.

The question is whether one or even both of those named is George Ransley, Smuggler, Ret’d. Certainly Captain Bats’ experience of command could have been useful in this exercise but he might have been thought a bit long in the tooth for serious bush bashing. And he was still a convict under sentence. If it wasn’t that George on the list it could only have been his eldest son, George junior. He at least was a free man but rather young (not yet 20) to be put in a position of responsibility. Perhaps the father was the Leader and the son the Volunteer. Or the other way round.

One thing is sure, for the time the Line was in operation (about 6 weeks from early October to late November 1830) Elizabeth Ransley must have been in a state of high anxiety. Whether it was on account of her husband, her son or both we’ll probably never know.

The Way to Freedom

Criminality tends to decrease with age and with parental responsibilities so George Ransley, middle aged property owner and a father many times over at the time of his arrest, was never the typical convict.103 This goes a long way towards explaining George’s choice to accept punishment quietly and serve his sentence with as little aggravation as possible.

In the whole of the time the Convict Department had him on the books (1827-1838) there was only one lapse, in 1833, when New Norfolk Magistrate Edward Dumaresq imposed the sanction of admonishment for the offence of 'disorderly conduct'. At the time George was assigned to his own wife.104 Surprising as this seems, it was not unusual at this period for a convict to be assigned to his/her spouse, but it was presumably an indulgence shown only to those whose behaviour had been exemplary.

While George Ransley's Conduct Record is a very sparse document an alternative source, the Convict Musters, is more slightly forthcoming.105 This indicates he had been assigned to Elizabeth by 1830 and had been granted a Ticket of Leave by 1833, very early for a convict serving a life sentence.106 [img] If the Muster record is to be trusted George Ransley, after narrowly escaping hanging for his crimes, ended up spending just over three years obliged to work for someone whose economic interests were not the same as his own. Not much to complain about there.

Once assigned to Elizabeth, George could focus on the serious business of supporting the couple's numerous offspring. While Matilda and George jnr, must have been financially independent from around 1831-32 that still left up to five sons and two daughters living at home. With that in mind George kept up the good behaviour and qualified for a Conditional Pardon in mid 1838, five and a half years after his Ticket of Leave.107

And They All Lived Happily Ever After?

Some English accounts of George Ransley’s smuggling career conclude with a few lines on his life in Van Diemen's Land. One of the most far fetched asserts that he ‘became a successful farm owner employing most of his smuggling colleagues and becoming comparatively wealthy in the process.’108 Henry Shore more soberly quotes a Tasmanian source concluding that George Ransley had ‘rented part of the estate of Captain -------, the farm was of 600 acres, with agricultural and grazing lands upon it. … He was regarded as a man of good character, and was respected by his neighbours.’109 Not surprisingly the truth lies closer to the latter than the former.

What is clear is that as soon as he could George resumed his former (legitimate) occupation – farming - on his own account. Elizabeth Ransley, or at least a 'Mrs Ransley' in the New Norfolk district had had other convicts assigned to her in the 1830s and by 1836-7 some convict labour was assigned to George direct.110 This suggests that he was farming on a scale that required extra hands even if he could not have been renting anything like 600 acres.

George was no soft touch as a master. Convict Adam Pursehouse (or Parsehouse) assigned to him in January 1837 was up before the local magistrate in May accused of neglect of duty and working for his own benefit.111 Pursehouse was sentenced to 3 months of hard labour and forbidden to return to the district.

Another name we have is that of Thomas Wilkinson, transferred from the service of Henry Savery in November 1837.112 Wilkinson's besetting sin was drink – unless it was just for a chat that he was ‘out of hours in a Public House’ on no less than three occasions while assigned to Ransley. On the last occasion Wilkinson made matters worse by ‘escaping from the constable’ and copped 14 days in the cells on bread and water. The magistrate, having been quick enough to throw the book at Pursehouse, was remarkably tolerant of Wilkinson despite his recidivism.

Ivanhoe!

No, not the novel written by Sir Walter Scott, but the property on the River Derwent at Plenty next door to George Thompson's Charlie’s Hope, later Cluan. During the 1840s two of George and Elizabeth Ransley’s sons, George jnr and John, were farming, presumably as tenants, at Ivanhoe.113 George jnr was still there at the time of the 1848 census.

There is evidence that for at least some of the time between George gaining a ticket of leave and 1848 the senior Ransleys were also tenants at Ivanhoe. This evidence comes from the register of convict assignments in the New Norfolk police district for 1833-1853.114 Like most historical documents it is not a perfect source. For a start there’s the small problem of having two George Ransleys as the register does not distinguish between father and son and convicts Pursehouse and Wilkinson are not even mentioned. But among the eight men assigned to ‘George Ransley’ there is one, labourer Edward Rogers, whose conduct record specifically notes that his assignment in May 1846 was to George Ransley senior, at Ivanhoe.115

At the top of the page listing the convicts employed by George Ransley the name 'Mr Jamieson' appears in pencil. David Jamieson was owner of Glen Leith, the property next downriver from Charlie's Hope. It seems possible that George Ransley may also have worked for Jamieson for a period in a supervisory role.

The Falls

Once they left Ivanhoe, probably around 1847, George and Elizabeth Ransley seem to have spent the rest of their lives at a place called ‘the Falls’.

Sometimes written as 'The Falls, New Norfolk' or 'The Falls of the Derwent', the Falls is, or was, a locality on the Derwent River two or three kilometers upstream from New Norfolk. Settlement at the Falls was early, probably around the same time New Norfolk itself, and troops had to be stationed at the Falls in 1817 to protect settlers from bushrangers, those escaped convicts who roamed the interior preying on isolated settlements.116 Bordering heavily timbered hills and close to water transport the Falls had been the site of a government sawmill until this activity was relocated to Port Arthur around 1830.

Despite the name no waterfall was involved but rather a set of rapids at which the Derwent could be easily crossed. From as early as 1827 there was a concerted effort to have New Norfolk's first bridge built there.117

About a mile and a half above the town ... navigation is entirely barred by a ridge of rocks, called in local parlance The Falls. These rocks are almost entirely under water, the river flowing swiftly in a broken current : they are of no great extent, and immediately above them the stream presents a deep and lengthened reach, again impeded by a similar obstruction.118

On modern maps a point on the river opposite the junction of the Glenfern and Glenora Roads is named as 'Falls Rapids'. The best I can work out is that the Falls as a place to live was more or less on the site of present day Lawitta.119The exact location is confused by the fact that the 'the Falls' refers to the river, so land on either bank could be 'at the Falls'. But it's most likely the Ransleys were on the Lawitta side amongst a cluster of small holdings.120 The other bank was characterised by large properties, one of which now houses the Bryn Estyn water treatment plant.

Captain -------

There are several possibilities as to the identity of the mysterious captain supposed to have been George Ransley’s landlord on 600 acres. The acreage of properties varied over time and it is not clear whether Henry Shore was referring to land at the Falls or further upriver. Van Diemen’s Land was not short of retired or semi-retired army officers speculating on land grants or trying their hand at farming. Among them was Captain Edward Dumaresq, the New Norfolk Police Magistrate, who owned land around New Norfolk.

If the reference was to George’s farm at the Falls I rather fancy Captain Richard Armstrong as the mystery man. Armstrong was an old India hand whose principal property, Bingfield, was on the site of the present day Valleyfield. He also had another 220 acres ‘at a distance of about 2 miles’ both of which sites could qualify as being ‘at the Falls’.121 In 1845 Armstrong’s land was for sale by reason of his insolvency and the advertisement specified that ‘nearly all [was] in cultivation and subdivided’.122

But another possibility exists. The principal lessee of Ivanhoe in the early 1840s was one John Peyton Jones.123 Jones had retired from the 63rd Regiment of Foot at the rank of captain on appointment as Police Magistrate at Westbury in July 1841.124 Westbury being a long way from Plenty Jones was obliged to look for someone to take over the four years of lease that were still to run.125 I wouldn’t suggest that George Ransley had the means to take on a the whole property (850 acres) but it’s entirely possible that he leased a part of it. The clincher for me is that John Peyton Jones was born in Lydd, Kent, in 1809, less than 20 kms as the crow flies from Aldington. Captain Jones was exactly the right age to have grown up listening to tales of the exploits of the Aldington Blues!

Farming at the Falls

Crops typical of the district at the time included wheat, oats, barley, corn, potatoes and peas.126 All of these were grown in the Kent of his youth, so George was on familiar ground. We don't know what livestock he ran but given his Romney Marsh heritage and local conditions it's a fair chance sheep were involved. In December 1842 three poor sods washing sheep at the Falls were drowned in the Derwent – proving that shepherding could be a risky business even after the threat of attack by Aborigines had passed.127

Drinking at the Falls

While it has since disappeared from view, the Falls must have been a relatively busy place. There are numerous newspaper references to farmers, tradesmen and small businessmen living at the Falls in the 1840s and 1850s and earlier. And wherever there was a river crossing, a pub was never far away. Innkeepers such as Niels Bastian ran their own punts and ferries, a sure way of ensuring a steady flow of drinkers, while they waited for the bridge that-never-was to be built at the Falls and make everyone’s fortune.

Bastian operated the Blue Anchor Inn at the Falls from at least 1827 and over the time George and Elizabeth lived there numerous other licensed premises came and went: The Jolly Ploughman (Anson family); The Fountain (Brooks); The Ark Inn (Davis);128 and The Rock Inn (Macdonald) amongst them.

It may come as no surprise to learn that a certain George Ramsley [sic] was granted a licence to sell wine and spirits at the Falls in 1838.129 It looks like George senior had another go as publican, this time at Fairfield House (the new name for The Ark Inn). The venture didn't last long - no doubt the margins weren't as attractive when the product had to be bought at market rates – and by 1840 the Fairfield licence had been transferred to William Ramsley.130 This is presumably the pub referred to as ‘Ransley’s Inn’ where an inquest was held that year for Mary Macdonald, the wife of the Rock Inn publican.131

In the absence of coincidence this William was George and Elizabeth's third son. A family enterprise close to the river would also explain why George jnr came back from the Styx to work at the Falls as a boatman between 1838 and 1840.132

William Ransley's tenure as innkeeper was equally shortlived. Fairfield seems to have been the property of Ann Bridger, founder of New Norfolk's Bush Hotel.133 A canny businesswoman, it's unlikely Mrs Bridger would have had much sympathy for a potential competitor struggling to pay the rent. In any event William Ransley, licensed victualler, New Norfolk, was the subject of insolvency proceedings in July 1841.134

Three of the Ransley girls were also connected to the pub trade. Ann’s husband, William Gundry, kept a pub in Geelong, in the colony of Victoria, Matilda was convicted of sly grog selling from her shop at the River Styx, while Hannah’s husband, George Rayner held the licence of The Flag of Truce, also at the Styx.135

George Ransley jnr may also have flirted with pub keeping. The handwriting is difficult to make out but he seems to have had three convicts assigned to him briefly in 1847 at the ‘Hamilton Inn’.136

And finally a John Bailey, licensed victualler, late of the Fountain Inn, at the Falls near New Norfolk, was subject to insolvency proceedings in 1842.137 It’s a common enough name but the possibility of yet another failed pub keeper in the family can’t be excluded.

1848 – The Rough with the Smooth

The first confirmation of George Ransley as actually owning property in VDL comes from the 1848 census, the earliest available for New Norfolk. There he was recorded as owner and occupier of a wooden house at the 'Fall'.138 By then George and Elizabeth, in their 60s, were living alone.

In the course of the 1830s and 1840s their children had grown up, moved away and married. Most of the boys were farming further up the Derwent, at Ivanhoe, Fenton Forest or Macquarie Plains.139 Matilda and Hannah were also in the Derwent Valley. Ann was the odd one out having married blacksmith and River Plenty poundkeeper140, William Gundry, and moved with him to Victoria.141

Edward, my direct ancestor, was the last of the children to marry, in 1850 to his first cousin Elizabeth Higgins, but he was living at Macquarie Plains by then and was not part of his parents' household in 1848.

Life seemed to be jogging along all right for George and Elizabeth. Their children presented them with grandchildren at a steady rate from 1832 and the family ties remained strong. George jnr christened his firstborn Elizabeth, while Matilda went one better and called hers George with Ransley as his middle name. George jnr completed the set in 1845 by giving son Edward ‘Bailey’ as middle name.

Some time in the 1840s Elizabeth Ransley’s sister Rhoda, now a widow, moved to the Derwent Valley. The sisters had obviously kept in contact since arriving together in 1829 but now could actually see each other from time to time. Rhoda remarried John Poole in 1846 at New Norfolk, witnessed by Robert Ransley and his wife Margaret.142 Following their marriage the Pooles lived at Fenton Forest where Robert Ransley had a farm so he seems to have been instrumental in Rhoda’s move, presumably encouraged by Elizabeth.

But not everything in the garden was rosy. Canny George Ransley, the man who had conjured up a farm, an inn and a profitable smuggling operation on the back of his own quick wits and a dash of luck was the subject in 1848 of insolvency proceedings.143

Insolvency was common in Van Diemen’s Land at every level of society and Edward MacDowell, the Hobart Commissioner of Insolvent Estates, was kept nicely busy. Much colonial land and other property changed hands to satisfy debts, in the process providing a tidy income for lawyers, newspapers and auctioneers.

The reasons for George’s financial difficulties are unclear, other than that he owed £269, a considerable sum, to a single (unnamed) creditor.144 It’s hard to imagine that such a debt could have accumulated from day to day expenses. Rather it suggests something in the nature of a failed business venture but this is a matter for speculation.

Presumably the parties came to a satisfactory arrangement under the supervision of Commissioner MacDowell as there is no sign of a property sale (assuming there was something to sell) and no indication that George and Elizabeth’s circumstances changed after this time.145

‘A Man of Good Character … Respected by his Neighbours’

The place of former convicts in VDL society was an ambiguous one and George Ransley's experience exemplifies this. While he or his children would not have been regarded as social equals by free settlers there seemed to be few barriers to emancipists participating in the public and economic life of the colony.146

In 1845 the leaders of the New Norfolk community called a public meeting at the Bush Hotel. It was provoked by proposed increases in the duty on the essential items of tea and sugar. Not only was George Ransley snr in attendance but he was invited to sign the meeting’s petition to the Lieutenant-Governor. While it seems that his signature was considered as good as that of the next man we can only speculate on what George made of the petition's condemnation of

that large portion of the expense of the police, gaols, and judicial establishments, required for the coercing of British malefactors, from whose labour the colony is allowed to derive no benefit, but is threatened instead with deep and wide spread moral evils147

having been so recently such a malefactor himself. Times were changing.

In 1854 George was signatory to another petition – this time to Queen Victoria herself – protesting at the puisne judge, Justice Horne, being passed over as Chief Justice in favour of the Attorney-General, Valentine Fleming.148 This petition was a sort of a microcosm of VDL society. Initiated by the Speaker of the Legislative Council, Sir Richard Dry, its signatories in the Derwent Valley range from Captain Michael Fenton MLC of Fenton Forest and Ebenezer Shoobridge of Valleyfield through to a certain Samuel Binlett, sheepholder, the Falls, and emancipist shoemaker George Nisbett, incidentally a former suitor of Matilda Ransley.149 At least four of the Ransley sons were also signatories.150

This is not to say that shepherd Binlett or cobbler Nisbett necessarily took a great interest in the quarrels of the VDL elite but the fact that they were invited, encouraged or browbeaten to sign says something about how the place operated.

Little did the Ransleys and their neighbours know that Judge Horne would soon be trying Matilda's husband Charles Fenton and eldest son, George, for trespass. His Honor made the comment, in finding the Fentons guilty, that 'this was the most flagrant instance of trespass that he had ever met in the whole course of his judicial experience.'151 There's gratitude for you.

George Ransley also gave to worthy causes: – 10 shillings to the Patriotic Fund got up in 1855 to help the widows and orphans of Britain's war dead in the Crimea.152 Neighbour George Nisbett gave £1 while George Ransley jnr and his brother Robert were contributors through the Native Youth Lodge at New Norfolk.153 These former felons and their children maintained an interest in the country which had expelled them long after that country had ceased to interest itself in them.

Death of Two Old Colonists

In all George Ransley spent nearly thirty years in Van Diemen’s Land. He lived to see the end of transportation (1853) and the renaming of the colony as Tasmania by 19th century spin doctors anxious to erase its unsavoury past.

Emblematic of these changes, George Ransley, transported to Tasmania as a criminal, was qualified to vote in the 1856 election for its new Parliament.154 We can’t be certain that he made it to the New Norfolk Court House to cast a ballot on 13 September as he died not long after on 25 October 1856 aged 77.155 [img death notice Courier 27 Oct] We can be sure though George would have had an opinion.

The cause of death was recorded as yellow jaundice which could have been symptomatic of any number of underlying conditions. The ubiquitous George Nisbett registered the death which was one less thing for Elizabeth to worry about. She had most of her children living not far away (principally around Bushy Park) with only two further away: Edward in the southern Midlands and Ann in Victoria.

Elizabeth survived her husband for two years before dying ‘of natural causes’, also aged 77, on 30 December 1858.156 Her death was registered by the undertaker at Back River (modern Magra). This suggests she had remained at her home at the Falls rather than, say, moving into New Norfolk or going to live with one of her children.

George and Elizabeth Ransley are buried at St John's the Evangelist, Plenty, as are their son John and daughter Hannah. The church is a few kilometers past the Falls as you head to Charlie’s Hope and Ivanhoe.

The Ransley Legacy

There’s evidence that the Ransley name was not forgotten back in Kent around Aldington.157 Some, if not all, transportees maintained contact with relatives left behind and most of those in the New World must have had a fairly positive story to tell.

We used to hear from him now and again. He did very well out there.158

Elizabeth’s brother Robert Bailey might have ended up cursing that he had not been charged with smuggling like the others and got himself transported to the colonies.159

One of Shore’s old timers related that Ruckinge native William Collins, reputed in some quarters as having informed on the Blues, was himself transported in 1842, for sheep stealing.160 Naturally he ended up in Van Diemen’s Land where he had the opportunity to catch up with John Bailey on his farm, ‘a fine place’.161 Collins later wangled a passage back to the England, where he spread the word of how some of the gang members had prospered in the New World.162

Shore also reports that two nephews of George Ransley were transported to Van Diemen's Land. Either this really was a family of incorrigible criminals or glowing accounts from across the seas were acting as the best possible incentive to transportation. One of the nephews must have been ploughman William Ransley from ‘Allington’ who left wife and children back in Kent when transported for horse stealing in 1840. In Van Diemen’s Land he managed to get assigned to Matilda Ransley’s husband Charles Fenton at the River Styx (1844) and George Ransley – probably snr - at Ivanhoe (1845).163 The family found ways of looking after its own.

George and Elizabeth’s family grew and prospered in Tasmania. By the time of George’s death the couple had more than 30 surviving grandchildren so their descendants are many and varied, starting with the numerous Ransleys who have peopled the Derwent Valley.164

Sons George, John and Robert in particular maintained the family tradition of fertility while daughters Matilda and Hannah boosted the numbers of Fentons and Rayners.165 Two of George and Elizabeth’s children, George jnr and Hannah, lived to see the dawn of the twentieth century, George dying in 1904 and Hannah in 1908.

A plaque in memory of George and Elizabeth Ransley was installed at the Plenty cemetery in 2010 by a number of their descendants.

1H N Shore The True History of the Aldington Smugglers. I am indebted to John Ransley of Queensland for a typescript copy of this work which in turn was made available to him by John Douch of Kent. The material was first published as a set of articles in the Kentish Express in 1902-3.

2Also known as the 'South Kents'. p. 59 John Douch Rough Rude Men Dover 1985. Opinion is divided as to whether the 'Aldington Blues' was a contemporary name or a later invention.

3A perfect example is Marian Newell's A Devil's Dozen, Epsom UK 2012.

4England Select Births and Christenings 1538-1975, ANCLIB accessed Nov2016.

5Elizabeth is recorded as having been 77 at the time of her death on 30 December 1858, which would have her born in 1783. TAHO RGD NN35/1859/5950.

6W Page (ed) The Victoria County History of Kent 1932 quoted by Jennifer Mills in 18th and 19th Century Mersham at pp. 3 & 8 accessed at https://mershamistery.wordpress.com/mersham-during-the-18th-and-19th-centuries/ November 2016.

7The exact number remains a matter for conjecture. There were several Bailey families living in the area around this time, and greater minds than mine have been puzzling for years over who belonged to whom.

8According to their respective convict records, TAHO CON23/1/1 Samuel, despite being John's nephew, was the older of the two men at the time of their arrival in Van Diemen's Land in 1827 – 41 as against 34 years old.

9The True History of the Aldington Smugglers p 108.

10The True History of the Aldington Smugglers p 105. This brother, like George, is reported to have worked as a wagoner, the 19th century equivalent of a truck driver.

11TAHO CON23/1/3. Description George Ransley.

12I am indebted to Mr John Ransley of Queensland for the information that follows although as I understand it most of the primary research has been done by others – thank you to them too!

13The marriage of George Ransley and Hannah Barns on 18 Jul 1779 at Warehorne is indexed in the Mid Kent Marriages Index 1754-1911 on www.woodchurchancestry.org.uk accessed Nov 2016. Warehorne is located between Ruckinge and Kenardington.

14England Select Births and Christenings 1538-1975, ANCLIB accessed Nov 2016.

15Edward Hasted, 'Parishes: Rucking', in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 8 (Canterbury, 1799), pp. 352-360. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-kent/vol8/pp352-360, accessed Oct 2016.

16Reproduced in 18th and 19th Century Mersham p.61. Around 1850 Edward Finn transcribed the journal kept by his father JA Finn, Mersham parish clerk and schoolmaster, for the period 1794-1818.

17Finn, 18th and 19th Century Mersham pp 60-61, writes at some length about the grief this pair caused their parents. Mr and Mrs Ransley (a highly respectable couple) had moved from Ruckinge to Mersham by the time their offspring met their end.

18Lord Teignmouth (HN Shore) & Charles G Harper The Smugglers. Picturesque Chapters in the History of Contraband London 1923 p.167.

19There seems to be a Court Lodge Farm associated with practically every village in the area, including Ruckinge, but John Douch in Rough Rude Men, p. 59 specifies the Aldington property.

20See for example Ordnance Survey Landranger 189 Ashford & Romney Marsh 1:50 000. For the history of Court Lodge Farm see pp 314-327 of Edward Hasted's The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 8. Originally published by W Bristow, Canterbury, 1799 and transcribed on http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-kent/vol8 accessed Nov 2016.

21John Douch Smuggling - The Wicked Trade, Dover 1980, p. 61. Aldington Frith is also sometimes written 'Fright' or 'Freight'.

221.80m and 1.85m respectively for the metrically minded. TAHO CON23/1/1. Description list Samuel Bailey and John Bailey. George 1.69m. TAHO CON23/1/3. Description list George Ransley.

23England Select Marriages 1538-1973, ANCLIB, accessed Nov 2016.

2416 July 1809. England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, ANCLIB, accessed Nov 2016.

25See here [link] for a list of Elizabeth Bailey and George Ransley's children.

26http://www.smuggling.co.uk/history_develops.html accessed Nov 2016.

27Mary Waugh Smuggling in Kent and Sussex 1700-1840 Newbury 1998 p.18.

28Accessed Nov 2016.

29The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.87.

30Most of the trade was with France but ports in Belgium and the Netherlands were also involved. For a thorough historical account see http://www.smuggling.co.uk

31The Wicked Trade, p.53.

32Opinions vary over whether Quested was leader of the gang at this time or simply a gang member.

33The Smugglers. Picturesque Chapters in the History of Contraband, p 110.

34For most of what follows on George Ransley's criminal career I have had to rely on secondary sources, many written long after the event. Access to the original contemporary records such as the reports of Customs officers is possible only in the United Kingdom. Maybe one day.

35The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, Chapter 2. By way of comparison it appears that a farm worker’s wage was less than £1 per week.

36The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p 118. The author claims to have personally obtained the reminiscences of George jnr but I have not yet worked out when the two could have met. There is no evidence that George jnr left Tasmania after arriving there in 1829.

37From the weapons, or bats, carried by some gang members.

38e.g. The Wicked Trade, p.68. The Bourne Tap, still a private home, is a listed building in Bilsington. http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-181643-the-bourne-tap-bilsington-kent#.WCX0rrWVuVs accessed Nov 2016.

39Reminiscences of an unnamed 'old timer', called as a witness in Ransley's trial and interviewed by HN Shore decades later. The Smugglers. Picturesque Chapters in the History of Contraband pp 168-9

40A figure given by Mr Justice Park at the trial of George Ransley and quoted by HN Shore in the The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.61. Newspaper accounts of the committal proceedings referred to runs involving 50-60 men.

41Around 17 litres. The 'tubs' were kept small for ease of handling and concealment.

42George Ransley jnr quoted in The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.118

43The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.8

44http://www.smuggling.co.uk/history_buying.html accessed Nov 2016

45Smuggled spirits were overproof to save space and needed to be diluted before they could be consumed safely.

46The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.88.

47The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.91.

48The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.88.

49The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.62.

50Married to Elizabeth Bailey's sister, Rhoda. Richard and Rhoda are also forebears of mine.

51Recollections of an 'aged acquaintance' The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.81.

525’7” is about 170cm. TAHO CON23/1/3. Description List George Ransley.

53The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p. 93-4.

54The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p. 95.

55The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.40. The original newspaper does not seem to have survived.

56Trivia time: Charles Bicknell (1751-1828) was the father-in-law of English landscape painter John Constable (1776-1837). https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/flatford/features/father-in-law-charles-bicknell accessed Dec 2016.

57A resident of Ruckinge as it happens.

58The Runners were the precursors of the Metropolitan Police force which was established 2 years later.

59Sadly, history does not record what that was.

60Reported in London newspaper the Morning Post, 25 Oct 1826.

61From Hellard's official report. The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p. 45.

62Hellard estimates the round trip at nearly 30 miles (about 48 kms).

63The names of the accused vary slightly from source to source so this list does not completely match up with the names of those later tried at Maidstone.

64Morning Chronicle, 28 Oct 1826.

65Morning Chronicle, 28 Oct 1826.

66The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.58.

67The next round of Kent executions was programmed for 5 February.

68If we are to take Shore’s account at p.59 literally the Solicitor-General who took part was Sir Nicholas Conyngham Tindal, later responsible for the introduction of the M’Naghten Rules for the trial of mentally ill offenders (one for the criminal law buffs).

69With the exception of Robert Bailey and one other gang member. Unlike the other defendants these two faced only one charge: murder. When the Crown decided to bring no evidence in relation that charge the judge was obliged to acquit them.

70Or perhaps someone on George IV’s behalf, the king by then being in severe physical decline.

71The True History of the Aldington Smugglers, p.64

72The remainder were held aboard the York at nearby Gosport.

73Elizabeth Ransley was baptised on 18 Feb 1827 at Bilsington while her father was on a prison hulk awaiting transportation. England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, ANCLIB accessed Nov 2016.

74'In 1827 and early 1828' according to Margery Kendon, Bilsington People 1800-1900, Ashford 1974, p.28

75TAHO CON23/1/3 Description List George Ransley. Each convict was assigned what was known as a Police Number which helped to identify them on their progress through the convict system.

76Governor Arthur to Under Secretary Hay 3 Sep 1827, Historical Records of Australia Series III, Vol VI p. 153.

77TAHO CON23/1/3 and CON31/1/34 Conduct Record George Ransley.

78Mea culpa! I have lost the reference for this piece of information, found many years ago, worse, I even failed to note the date. Despite this I am pretty confident of its accuracy.

79George Thompson arrived free per Medway. HTG 17 Mar 1821. TAHO CSO1/1/368/8375 Colonial Secretary's Office General Correspondence.

80See Jennifer Parrott, ‘Agents of Industry and Civilisation: The British Government Emigration Scheme for convicts' wives, Van Diemen's Land 1817-1840’, Tasmanian Historical Studies Vol 42, 1994, p25ff.

81In office 1824-1837.

82See Parrott article for an entertaining account of the three way tussle between Arthur, his bureaucrats and the Colonial Office.

83The Colonial Secretary's Office file TAHO CSO1/1/368/8375 notes that the Ransley family had been sent out 'without any application having been received by the Secretary of State for them'. Arthur’s letter to the Secretary of State in support of George Ransley’s application was dated 10 October 1828, the Harmony having already sailed. TAHO GO 26/3 p.154. The paperwork was finally received in London on 11 Apr 1829, well after Elizabeth had reached her destination. Historical Records of Australia, Resumed Series III, Vol VII p.571

84Bilsington People 1800-1900 p.28. This largesse was presumably spread across the Ransley, Higgins and Giles families, all 'on the parish' of Bilsington, and all of whom left aboard the Harmony. Just to keep things in the family it appears that Mary Giles' mother-in-law was a cousin of the Baileys.

See https://lynnesfamilies.wordpress.com/aldington-smugglers/charles-giles/ accessed November 2016

85See [link Bailey-Higgins] for more detail.

87Cap Verde, off the West African coast, was then a Portuguese colony. Admiralty and predecessors: Office of the Director General of the Medical Department of the Navy and predecessors: Medical Journals; ADM 101/32/4. Harmony Surgeon Superintendent’s Journal. ANCLIB accessed Nov 2016.

88Henry Melville, VDL Comprehending A Variety of Statistical & Other Information Likely to be of Interest to the Emigrant as Well as to the General Reader, London and Hobart, 1833, p.149. Accessed from Googlebooks Feb 2017.

89HTG 27 Jul 1822 but the first reference to a formal grant I can find is in the Colonial Times of 18 Nov 1825.

90Convict John Ince. HTC 10 Jul 1830.

91The modern address is 50 Onslows Road, Plenty.

92Assuming they did. This was supposed to be a prerequiste of the scheme but I have been unable so far to find the documentary evidence for George Thompson supporting Ransley’s application.

93K R Von Stieglitz, A History of Hamilton, Ouse & Gretna, Launceston, 1963, p.30.

94I can recommend Nicholas Clements, Black War. Fear Sex and Resistance in Tasmania, St Lucia, 2014 for a fascinating account of this period 1824-31.

95Colonial Times 28 May 1830.

96To say nothing of the much more acute risk to the Aboriginal population.

97Partly due to their vulnerability but also because shepherds and other isolated assigned servants had a reputation for acts of brutality towards the Aborigines.

98See Black War. Fear Sex and Resistance in Tasmania for a detail.ed account.